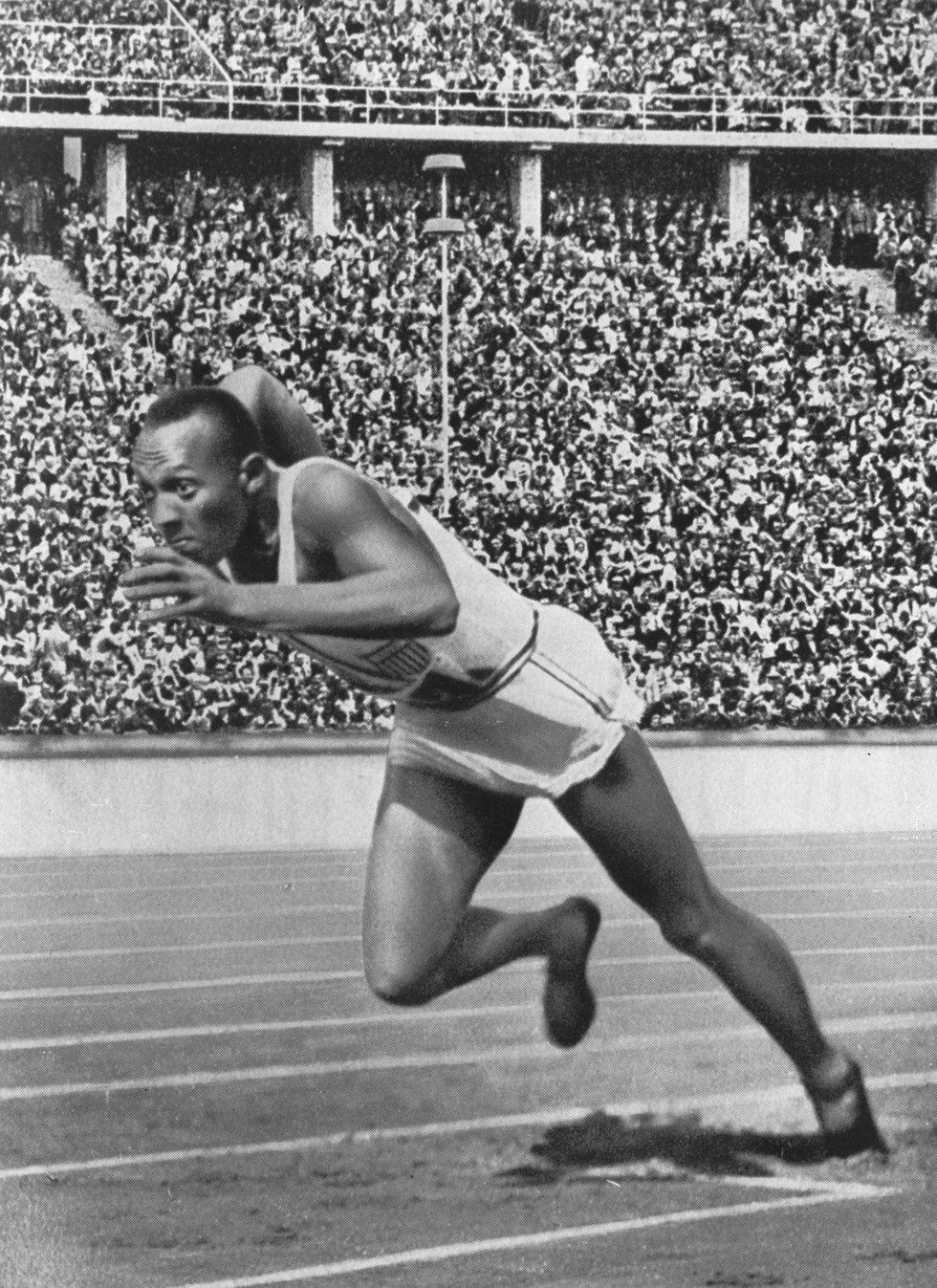

He made more money than the vast majority of his fellow Americans in the dry-cleaning business, at Ford Motors, working for the state of Illinois but the windfall he expected in the aftermath of his Olympic heroics never materialized. In the first fifteen years after his athletic career ended, he had struggled to find his way, professionally and financially. For Owens, the appearance with Murrow was emblematic of his enhanced stature. Here, Murrow thought, was a legitimate American hero, the man who had humbled the Third Reich. Despite the fluff, Murrow was eager to speak with Owens, whose legend had grown significantly since 1936. No one confused Person to Person with See It Now, Murrow’s other show on CBS, the one on which eighteen months earlier he had neutered Senator Joseph McCarthy. He still held the world record in both the broad jump (now called the long jump) and the 4 x 100-meter relay though both records had been set in the mid-1930s.įor his part, Murrow was readying himself for another half-hour of banalities. In fact, just a few months earlier he had run 100 yards in 9.9 seconds, less than a second slower than his personal best. In his conservative jacket, flannel slacks, white shirt, and dark tie, he could have passed for a fifty-year-old. More than 20 million Americans would watch as Murrow spoke from a studio in New York via satellite, first with Owens and his family, and then, in the second half of the show, with Leonard Bernstein and his.Ī forty-two-year-old father of three, Jesse Owens weighed twenty- five pounds more than he had in Berlin in 1936, when he had turned in the most indelible performance ever at the Olympic games. Murrow of CBS, on his celebrity interview show Person to Person. In a few minutes, Owens would be talking live on national television with Edward R.

As he smoothed out his pencil mustache and slicked back his hair what little was left of it a dozen technicians put the finishing touches on what had been an allday job, wiring and lighting the Owens home. central time on September 23, 1955, in a handsome townhouse on Chicago’s South Side, James Cleveland Owens slipped into a tweed jacket and sat down in a straight-backed chair. He is the son of the award-winning journalist Dick Schaap. He has also appeared on ABC's World News Tonight and the CBS Evening News. An ESPN anchor and national correspondent, his work has been published in Sports Illustrated, ESPN the Magazine, Time, Parade, TV Guide, and the New York Times. Jeremy Schaap is the author of the New York Times bestseller Cinderella Man.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)